Not a member of Medium? Read every story from Paul Thomas Zenki (and thousands of other writers on Medium) by subscribing today. Your membership directly supports Paul Thomas Zenki and other writers you read. Click here to join.

The Unspoken Reason Slavery Reparations Won’t Happen

Why neither liberals nor conservatives will allow reparations …

In cities across the US — from Santa Monica, CA, to Athens, GA, to Evanston, IL — Americans who had their lives upended and their opportunities dashed by bigoted policies and actions by their own governments are receiving at least some measure of redress for their losses. But reparations for some two centuries of official white supremacism at the national level are still just so much talk.

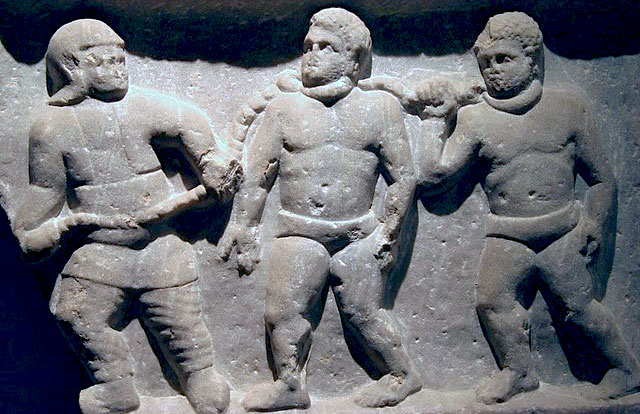

The reality of American white supremacist policy is undeniable. And although enslavement is nothing new in this world, stretching back even before the dawn of recorded history, the trans-Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries took an especially brutal form — race-based, lifelong, inherited chattel slavery.

Enslavement historically was often exacted as a penalty, for opposing a siege or incurring debts or breaking laws or just being on the losing side of a war, although it was also an expedient means of procuring labor for imperial works or keeping a lid on disfavored populations. Some cultures imposed time limits on enslavement, granted limited rights to slaves against exceedingly cruel treatment, allowed enslaved persons to purchase their freedom or even let former captive slaves join the free culture and intermarry.

But slavery in the American colonies and in the US was the worst of the worst:

- Status as a slave was based on race. If you were a “negro of the African race” you were deemed inherently inferior to “white” persons and thus deserving of enslavement. Even if you were emancipated, you still had no guaranteed rights as a citizen.¹

- It took the form of “chattel slavery.” Once enslaved, you were treated as personal property with no human rights at all, including the right to protest your enslavement even if it violated the law, as in the case of “recaptured” freedmen.

- Status as a slave was permanent. Unlike indentured servitude, enslavement was a life sentence, except at the whim of the enslaver.

- Enslavement was hereditary. If you were enslaved, your children would be born enslaved and live out their lives as another person’s property. Parents and children could be split apart and sold off at any moment.

Of course, the institution of slavery was banned in the US (except for prisoners, mind you) in 1865. Yet that was not the end of official white supremacy, which lived on in segregation laws, exclusion of black Americans from GI Bill benefits, and other Jim Crow policies. I’ve met young people who are genuinely surprised to know that white supremacy as official state policy only ended during my lifetime.

Which means there are people alive today who are the direct victims of state-imposed bigotry, like the “descendants of Linnentown” in Athens, GA, who had their land taken and their homes destroyed, and in some cases their families broken apart, so the University of Georgia could build new dormitories for white students while actively resisting desegregation. Why, then, are there no plans on the table for national reparations?

A different kind of identity politics

It’s easy to get caught up in the brouhaha over whether reparations should be made, over the supposed moral and ethical issues of imposing what amounts to a national tax for racial redress, and supposedly practical questions of economics, whether the nation “can afford” to pony up financially. But none of that is what dooms reparations.

Even if everyone were to agree that financial redress was both ethically and legally merited and economically affordable, we would still be unable to pass the necessarily legislation. And it all comes down to who gets paid and how.

Think about it for a moment — how would we, as a nation, establish a workable means of identifying who is eligible for redress?

- If we demand that a person demonstrate actual damages, in any form whether that be ancestry or connection with incidents of official bigotry, we will be placing an unworkable burden precisely on those most likely to deserve compensation in the first place. At the same time, we will saddle everyone with the expense of the sprawling bureaucracy required to process claims and avert fraud by ineligible parties.

- If we base reparations on racial identity, on the grounds that even recent immigrants to this country are faced with economic and social roadblocks rooted in racial biases born of the nation’s history of official white supremacy, then we are required to craft state policy defining who, for example, is and isn’t “black” — one which satisfies all those who identify as black while effectively shutting out opportunistic non-black hucksters. Even if a computer-readable definition of blackness could be conjured up, which I seriously doubt, can we realistically imagine tying reparations to some sort of National Black Registry, especially right now when we’re faced with the very real possibility of a proto-fascist party taking control of the reins of power?

There is, I believe, a solution to be had, but I’m not optimistic that it can be made palatable to the political right or left in today’s America.

Martin in the middle

When it comes to issues of race and their related policies, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. inevitably ends up being claimed by all sides as a champion for their views. Yet despite anti-reparationists’ propensity to cite King’s famous remarks on judging ourselves by the “content of [our] character,” the record is clear that he was an ardent advocate for financial redress:

At the very same time that America refused to give the Negro any land, through an act of Congress our government was giving away millions of acres of land in the West and the Midwest, which meant that it was willing to undergird its white peasants from Europe with an economic floor. But not only did they give the land, they built land grant colleges with government money to teach them how to farm. Not only that, they provided county agents to further their expertise in farming. Not only that, they provided low interest rates in order that they could mechanize their farms. Not only that, today many of these people are receiving millions of dollars in federal subsidies not to farm. And they are the very people telling the black man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps. This is what we are faced with, and this is the reality. Now, when we come to Washington in this campaign, we are coming to get our check.

Yet this is not the whole story. And I mention Dr. King precisely because I believe his vision for a practical solution to meaningful redress for official white supremacist policy in the US is still workable — a combination of local reparations for specific demonstrable injustices, such as the destruction of Pico and Linnentown, with a national campaign to reduce rampant and growing wealth disparity and provide direct relief from poverty.

Here is Dr. King writing in his 1964 book Why We Can’t Wait:

No amount of gold could provide an adequate compensation for the exploitation and humiliation of the Negro in America down through the centuries. Not all the wealth of this affluent society could meet the bill. Yet a price can be placed on unpaid wages. The ancient common law has always provided a remedy for the appropriation of the labor of one human being by another. This law should be made to apply for American Negroes. The payment should be in the form of a massive program by the government of special, compensatory measures which could be regarded as a settlement in accordance with the accepted practice of common law. Such measures would certainly be less expensive than any computation based on two centuries of unpaid wages and accumulated interest. I am proposing, therefore, that, just as we granted a GI Bill of Rights to war veterans, America launch a broad-based and gigantic Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged, our veterans of the long siege of denial.

Three years later, in Where We Go from Here, Dr. King elaborated:

In the treatment of poverty nationally, one fact stands out: There are twice as many white poor as Negro poor in the United States. Therefore I will not dwell on the experiences of poverty that derive from racial discrimination, but will discuss the poverty that affects white and Negro alike….

I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective — the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.

Our nation’s adjustment to a new mode of thinking will be facilitated if we realize that for nearly forty years two groups in our society have already been enjoying a guaranteed income. Indeed, it is a symptom of our confused social values that these two groups turn out to be the richest and the poorest. The wealthy who own securities have always had an assured income; and their polar opposite, the relief client, has been guaranteed an income, however miniscule, through welfare benefits.

The contemporary tendency in our society is to base our distribution on scarcity, which has vanished, and to compress our abundance into the overfed mouths of the middle and upper classes until they gag with superfluity. If democracy is to have breadth of meaning, it is necessary to adjust this inequity. It is not only moral, but it is also intelligent. We are wasting and degrading human life by clinging to archaic thinking.

Obviously, bringing American conservatives around to this way of thinking would be a challenge, to say the least. But I also fear resistance from liberals to this approach, on the grounds that it divorces economic redress, on the national scale, from racial injustice. In other words, if whites are included, are we even talking about reparations anymore?

I think the unavoidable answer is no, we’re not. And this is why I believe reparations for slavery and Jim Crow are unachievable under any administration. Paradoxically, in order to have a real shot at tangible redress, even if liberals could win a supermajority in Congress with a progressive Democrat in the White House, the notion of specific compensation for the evils of officially sanctioned white supremacy would have to be abandoned in order for reparations to be provided in practice.

Once again, it comes down to our willingness to sacrifice our ideologies on the altar of political practicality. And right now, anyway, I see precious little indication that either liberals or conservatives have the stomach for such concessions.

¹Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857)

Header image: Emancipation and Freedom Monument, Richmond, VA (Wikimedia Commons)

Paul Thomas Zenki is an essayist, ghostwriter, copywriter, marketer, songwriter, and consultant living in Athens, GA.