Information Is Making Fools Of Us All

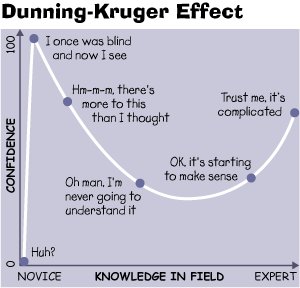

Perhaps you’ve heard of the Dunning-Kruger effect? If not, here it is in a nutshell….

People who only know a little about something tend to overestimate their understanding of it, while experts tend to underestimate their own expertise.

That may seem strange at first glance, but when you stop and think, it makes sense. When you’ve only learned a little, you don’t know what you don’t know. The landscape is simple and pastel. You think you’ve got it.

But the more you learn, the more details you see, and the better you come to understand there’s a lot more detail that you can’t see.

There’s a famous graph of the KDE that’s easy to find in many variations across the web. Here’s one version I cribbed from Coert Visser, who cribbed it from somewhere else:

This phenomenon presents a problem for all of us in the “information age”, because the more complex our world gets — the more we know about the universe, the more complicated our technology — the more we find ourselves on the left end of that curve there, knowing just enough to be dangerous.

Back in ancient Greece, if you were fortunate enough to be educated, you could pretty much know how everything worked. You might not be able to cast a bronze or pave a street or build a lighthouse, but dammit at least you could understand how these things were done. And what was a mystery to you — such as what the stars are made of or why the rain falls — was a mystery to everyone, so you might have been ignorant but you weren’t stupid.

Today, on the other hand, literally nobody has the remotest hope of understanding even 1% of modern science and tech, much less the oceans of information in circulation about politics, culture, art, even food. But almost all of us have access to just enough information to feel like we do know what’s going on.

Hell, I don’t even know how my vacuum cleaner works. Or what my state legislature is doing. Or which insurance plan is really best for me. Or how the economy functions. And yet all these things, and thousands more, determine my life in this human zoo we’ve built for ourselves on this planet.

But admitting that I am, relatively speaking, an utter ignoramus isn’t particularly flattering.

So instead, I imagine myself to be a right smart fellow, highly educated, richly informed, in control of what’s going on. I vote, I read the news, I went to college. I’m a fine specimen of homo sapiens, which after all is Latin for “wise man” — see, I knew that — and my destiny is my own.

Which is a fine steaming load of bull. In fact, I’m an idiot, at the mercy of forces beyond my control. Beyond all of our control.

Yes, we lament the abundance of fools. The deniers, the saps, the hopelessly gullible. Just look at them all, posting their ignorant comments, voting for all the wrong people, spouting their eye-rolling nonsense in the breakroom. Can you believe it? And yet the world we now live in, and have no real choice but to live in, is utterly beyond anyone’s comprehension, even though it’s us who created it!

We are all, each of us, at the same time confident and incompetent. Because we make the artificial world that we inhabit, we get the sense that we must be the masters of it. But we no more control it than the drops of water control the waves of the sea.

And until the next Dark Ages, the situation can only get worse. The more we as a species discover, the more we know, the more devices we invent, the more ignorant we as individuals will become, and the more deluded we will be about our own competence.

Which means that we can expect the choruses of foolishness to grow more raucous. Science denial, political extremism, conspiracy theories, urban mythology, all of these scourges will increase rather than abate with time. Not only that, but our technological advances will continue to outstrip our collective ability to make wise political choices about them. Useful progress will be shouted down while dark developments will go widely ignored as they come to fruition.

When the framers of the US Constitution assured the right of free speech, they did so on the assumption that the best remedy for bad information is good information. But they did so at a time when information was relatively rare. Now that it has become so abundant that everyone expects it to be free to all, we are finding out the hard way that information in such abundance is, in and of itself, a stumbling block to understanding.

Image by Ross Angus

Read every story from Paul Thomas Zenki (and thousands of other writers on Medium).

Paul Thomas Zenki is an essayist, ghostwriter, copywriter, marketer, songwriter, and consultant living in Athens, GA.