The Confederate “Stars & Bars” Is Still the Flag of One US State

It’s not just ON the flag, it IS the flag …

Last summer I heard a radio journalist say Mississippi was the last US state with a Confederate emblem on its flag. That flag has since been retired, but the reporter was wrong. The Confederate “Stars & Bars” still flies over one US state to this day.

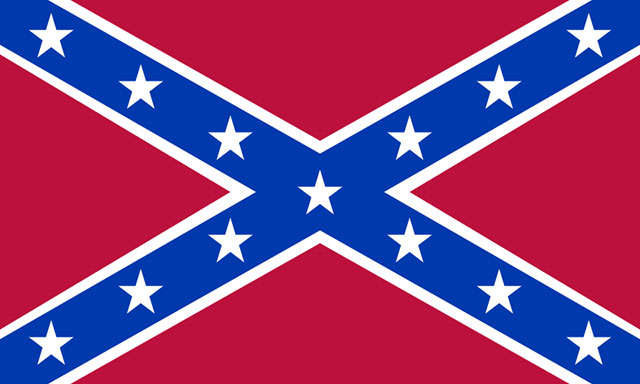

Now first I should correct a common misperception about the Stars & Bars. This ain’t it:

That is the second Navy Jack of the CSA, a rectangular version of a popular Confederate battle flag designed after the First Battle of Bull Run (aka First Battle of Manassas) when similarities between the Union and Confederate banners caused confusion among the fighting men. It is commonly referred to as the Rebel Flag, and often mistakenly called the Stars & Bars.

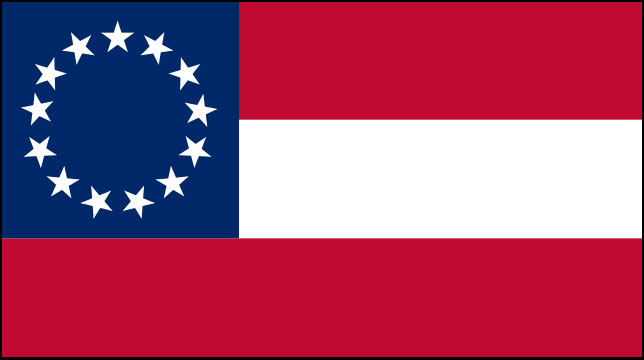

This is the actual Stars & Bars, first official flag of the Confederate States of America, specifically the 13-star version which flew from 1861 to 1863:

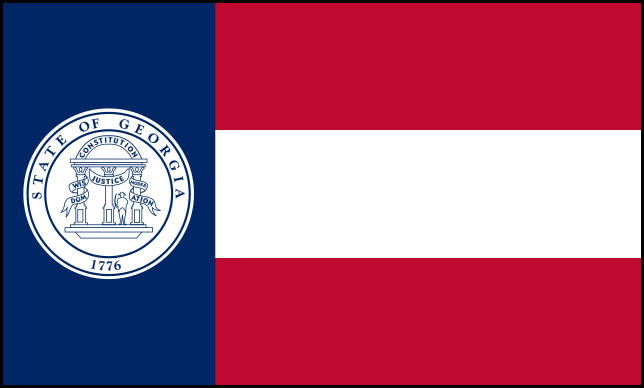

And this is the current flag of the State of Georgia, which is the Stars & Bars with the state coat of arms slapped on it:

Hard to say that’s not a Confederate emblem right there.

So how did that flag come to fly over the state of Georgia, and why do so few people notice it’s a Confederate flag?

Well, for most of my life, this was Georgia’s flag:

That flag, combining elements of the Stars & Bars and the Rebel Flag, was adopted pursuant to a bill introduced by state senators Jefferson Lee Davis (yes, his real name — I swear, you can’t make this stuff up with a monkey wrench) and Willis Harden in the wake of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education US Supreme Court decision and subsequent public turmoil over ending segregation of black and white students in public schools. But the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta focused more attention on the state symbol than it could withstand, and by 2001 it had been scrapped as fears of economic boycotts loomed.

For two years, the state flew a banner so ugly I refrain from posting it here and will only quote the North American Vexillogical Association’s verdict that it “violates all the principles of good flag design.” (That’s right, all of them.) In 2002 Governor Sonny Perdue — yup, “Sonny” — was swept into office on the flag issue, and in the first year of his administration the current flag replaced the so-called “Barnes rag.”

The idea Perdue campaigned on was that Georgians would be allowed to choose a new emblem. What actually wound up happening was folks were given a choice between what was literally the current ugliest flag in North America and a design put forth by the state General Assembly. Oh, and if the Barnes flag did happen to win, it would be forced into a runoff with the 1956 flag, a requirement not visited upon the new design. Seeing as how their contender could hardly help but prevail no matter what it was, the honorable members of the Georgia legislature opted to dredge up the banner of “the first [government] in the history of the world,” to cite the CSA’s Georgian vice president Alexander Stevens, founded “upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery — subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition.”

Of course, this is not how the design was promoted at the time. Rather, it was sold as a revisit of the pre-1956 flag, which itself had been an homage to the Stars & Bars, designed by a former Confederate colonel.

But this was something akin to claiming that Gus Van Sant’s 1998 scene-for-scene remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho was somehow inspired by Psycho II. The supposed tribute to Georgia’s pre-Brown-v-Board heraldry notably managed to undo every single element, save the coat of arms, which had distinguished it from the Confederate national flag in the first place. The design won with 73% of the vote.

One the one hand, a good chunk of the citizenry simply didn’t know what the official Confederate national flag looked like to begin with, and had no earthly idea they were voting for it. On the other hand, quite a few of those who knew what it was had no objection to adopting it, while some who recognized it felt it was better to go ahead and vote for it in the first round than to reject it and risk having the 1956 flag win in round two.

And so the emblem of the CSA still flies over an American state. And even journalists on nationally syndicated news programs don’t see it for what it is.

In many ways, the transition is emblematic of how white supremacy itself has changed its trappings in America over my lifetime. When I was young, dog whistles and microaggressions were not the order of the day. Hell, the Klan had a float in my town’s Christmas parade, for Pete’s sake. The entire point of white supremacy was to be in everyone’s face, to call the shots, to let everybody know what their place was and dare any soul, white or black, to say different.

By the turn of the century, though, white supremacy had gentrified behind a facade of plausible deniability. Overt racism was no longer acceptable in polite company, but then again it didn’t have to be. Probably the most succinct summation of the shift spilled from the lips of veteran Republican strategist Lee Atwater some four decades ago. (Note: This clip contains racial slurs.)

You start out in 1954 by saying, “******, ******, ******.” By 1968 you can’t say “******,” that hurts you, it backfires, so you say stuff like “forced busing,” “states’ rights,” and all that stuff. And you’re getting so abstract now, you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is, blacks get hurt worse than whites.… Obviously, sitting around saying, “We want to cut taxes, we want to cut this,” is much more abstract than even the busing thing and a hell of a lot more abstract than “******, ******.” Any way you look at it, race is coming in on the back burner.

The recent Trump administration and its supporters pushed these tactics to their utmost limits, with stunts like a national convention stage layout in the shape of a Nazi emblem. Being caught is part of the game, spreading the word to fellow travelers who missed the live play while simultaneously flaunting the impotence of opponents who in the end are powerless to prove anything or stop it from happening again.

Personally, I’d like to see the current Georgia flag given the old heave-ho. Hell, I wouldn’t even mind bringing back the ugliest flag on the continent to get rid of it. Trouble is, in an era when Georgia’s governor signs a voter suppression bill beneath a painting of a plantation house while a black legislator is arrested for knocking at the door to the room, I’m afraid to find out what other symbols from the past might be resuscitated to replace it.

Header image: Public domain

Read every story from Paul Thomas Zenki (and thousands of other writers on Medium).

Paul Thomas Zenki is an essayist, ghostwriter, copywriter, marketer, songwriter, and consultant living in Athens, GA.